Fanfare for…who exactly?

Exploring Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man

“December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”

-Franklin D. Roosevelt

In the months following the USA’s entry into World War II, all corners of society were in some way pressed into service. Whether through the purchase of war bonds, planting victory gardens, or donating scrap metal, there was an expectation that anyone, no matter their social status, could contribute to the war effort even if it was simply through a belief in the righteousness of the American way.

Alongside the steelworkers and automakers, artists and musicians took up the cause in their own ways, large and small. The conductor Erich Leinsdorf, who emigrated to the USA in 1937, was drafted into the US Army during his inaugural season as music director of the Cleveland Orchestra. Leinsdorf dutifully answered the call to his government, though this interruption cost him his standing at the Cleveland Orchestra; he resigned shortly after his honorable discharge. Arturo Toscanini, who lived in America during his directorship of the New York Philharmonic and NBC Symphony, had a history of antifascist statements and actions, including a refusal to perform the fascist hymn in 1931, which led to his being assaulted by thugs of Mussolini. During World War II, Toscanini assisted Jewish refugees, conducted benefit concerts, and used his bully pulpit as the music world’s brightest star.

Eugene Goossens, conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, had the idea of commissioning (for no pay) American composers to write fanfares which would begin each concert during the season. Gotta give him credit for consistency…. Goossens organized an identical project during World War I in his native Britain, utilizing composers from his homeland.

“[i]t is my idea to make these fanfares stirring and significant contributions to the war effort….”

– Eugene Goossens

The three aforementioned musicians were all European immigrants to the United States. Copland was a first generation American, whose birth year of 1900 suggests the hand of destiny, in ordaining him the foundation of American music for the century to come.

Copland’s choice of the title “Fanfare for the Common Man” was the result of a rather uncommon contemplativeness on his part with respect to finding the right name for a composition. This was a composer who until then had been perfectly happy to deliver his music into the world with bland descriptive titles drawn from the formal structure or purpose of the work (e.g. Symphony no. 1, Piano Variations, etc.) After considering and rejecting names that suited perhaps a more overtly nationalistic composition (Fanfare for Four Freedoms, Fanfare for the Airmen, Fanfare for a Solemn Ceremony, etc.), Copland wisely rebuffed Goosen’s frantic requests to send him the tardy composition. He took several months more to work on the issue, and in that time witnessed a speech made by vice president Henry A. Wallace proclaiming the dawning of the “Century of the Common Man”. In the speech, Wallace strongly rejects American exceptionalism, encourages collective bargaining, and urges the free people of the world to reject unfettered free enterprise.

“There can be no privileged peoples. We ourselves in the United States are no more a master race than the Nazis.”

– Henry A. Wallace

These ideas appealed to Copland, himself a leftist. He liked the idea that his composition could avoid overt nationalism and instead celebrate the common people who fought and labored to free the people of Europe from despotism. And so Copland informed Goossens that his composition would be titled Fanfare for the Common Man.

Copland’s Fanfare is a masterpiece. Over 80 years since the premiere, strains of it’s musical DNA appear in a wide range of compositions. A sense of hope, striving, and righousness, borne on a soft but powerful wind carries the listener from start to finish.

Despite the piece’s aesthetic straightforwardness, which can enrapture even the most casual listener, the musical material is extremely sophisticated. The plaintive and evocative open notes of the trumpets and horns defy any regular rhythmic pattern, and repetitions of phrases are often modified by small but impactful amounts. Although written in an overtly popular style, the technique of the composer was state of the art.

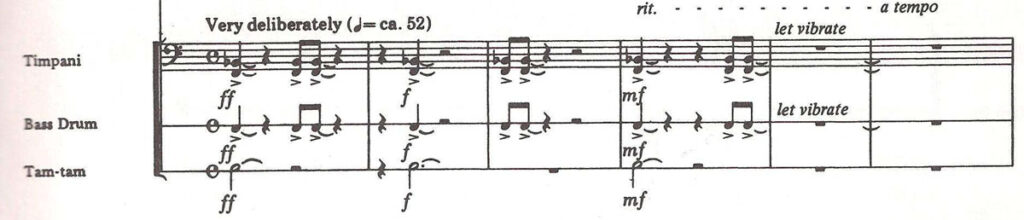

To me, the opening percussion strokes serve several purposes. They capture the audience’s attention through a show of force, allow us to appreciate the percussionist’s arsenal from a safe distance. But they also establish a rhythmic pulse….or do they?

Not exactly something you can tap your foot to. At the slow tempo of 52, the percussion hits appear random, and the only constant is that the dynamics and speed diminish and retreat into the distance. By the time the unison trumpets come in measure 6, I feel a sense of uneasy anticipation for what is to come. What eventually does come is a noble trumpet entrance, spare and abstract. It could be perfectly at home in the 12th century proclaiming the entrance of a king, or in hundreds of other musical settings. But what is certain, is that the character is not threatening. Many have remarked on the feelings of aspiration, righteousness, and exploration it evinces for them. For a more hands on and useful exploration of the musical material and some light analysis, there will be a supplemental video posted here in the coming days.

–Gregory Robbins