STOP WORRYING AND START LOVING THE WALTZ

They don’t want you to know how good light music is

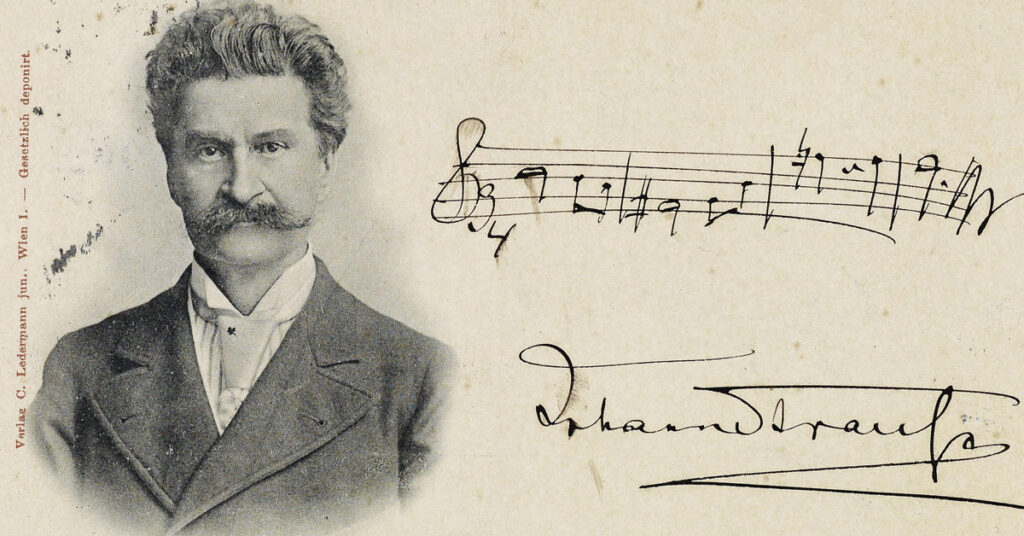

Luckily for us, there lived not just one, but TWO excellent Johann Strausses: Sr. (1804–49) and Jr. (1825–1899), who are the heroes of this blog post. While the younger Strauss has thoroughly eclipsed the elder in popularity and acclaim, both were shining stars of the Viennese music scene.

If the question is: how do you rise head and shoulders in popularity over contemporaries like Brahms, Schumann, Rossini, and Wagner, then the answer is apparently to be a chill guy and not take yourself too seriously. By writing music for parties, dances, and imperial events, Joseph Lanner, Strauss the elder, Strauss the younger, and a few other waltz pioneers carved out a practical musical and economic niche that insulated them from any expectations of high artistry or the haughty nonsense that come with that sort of thing. Along the way, their music swept away not only hometown Vienna, but spread like a wildfire across the European continent and even to the USA.

(Cockney accent) “Ahh I love this stuff!!!”

— Bramwell Tovey to yours truly, overcome with emotion after conducting Lehár with the New York Philharmonic. Yes this is a real quote.

One could be forgiven for imagining that the waltz, as exemplified by the heroes of this post, simply floated into being from the very cream puffs and perfumed kerchiefs that swirled around the ballrooms of upper class Viennese. And sure, the ambient Viennese dialect, culture, and signature Weltschmerz infused the moods, contours, and melodies of the form. Yet the distinctive Viennese waltz did not appear by magic. It arose through the deliberate, almost blue-collar musical craft of Strauss Sr. and Joseph Lanner, who transformed the rustic ländler, German dances, and other popular 3/4-time favorites of the Viennese public into something new.

Strauss Sr. should never have ended up a musician. His innkeeper parents were troubled by his early artistic aspirations, fearing the prospect of their son becoming a “dinner musician (Abendsmusiker),” or someone who performed all day and night at a restaurant or casino, in exchange for food and lodging. Such was, in their minds, the best case scenario in the career of an aspiring freelancer in those days. But fate intervened, and Johnny’s (Schani’s) early and amateur efforts on the violin were deepened by a fortuitous meeting with the teacher Johann Polischansky, who put him on a path towards musical relevance. The rather humble musical training that Strauss the elder received would later be put into stark contrast with that of his son, whose sophisticated musicianship afforded him a much more varied and ambitious compositional palette.

Sr., through his militant rehearsal methods, extensive touring, and unvarnished compositional approach, distilled and married the component elements of the waltz form to his own voice so completely, that he could adapt them to an endless number of musical or programmatic occasions, without losing their Straussian flavor. That’s why many of the lesser known Strauss waltzes (by both father and son) have names that reference the occasion of their commissioning or some event in their lives. (Student Union Waltz, Farewell to America Waltz, Going to the Grocery Store Waltz, etc). Both Strausses also had a habit of waiting until the morning that one of their compositions was going to be premiered before starting work. To mitigate this, they employed an army of copyists and arrangers who would even go so far as slicing up the manuscript score, so that they could all work as a team to complete the parts. Partly due to this, almost no original manuscripts have survived.

It should also be noted, that Strauss the elder put up extraordinary resistance to the idea of his son becoming a musician. This was no passing fit of misguided paternal career advice; Papa Strauss took extreme measures to prevent (and would later work to sabotage) the musical growth of his son. But persistence paid off for Jr., and on October 15, 1844, Johann Strauss Jr. led his very own orchestra in a debut at Dommayer’s Casino: an event which would ultimately lift the careers of both father and son.

So where to start?

Just start with the so-called “concert” waltzes of Johann Strauss II. The Blue Danube, Künstlerleben (Artist’s Life), and Voices of Spring are some of my favorites, and it’s hard to go wrong with any of them. The polkas, galops, and marches are similarly addicting.

Here’s a playlist I put together to start:

And don’t forget about Die Fledermaus – if you have a free afternoon bask in it’s shameless fun and richly varied score. It’s a great reminder of how complete of a composer Johann Strauss II was.