STOP WORRYING AND START LOVING THE VIENNESE WALTZ

They don’t want you to know how good light music is

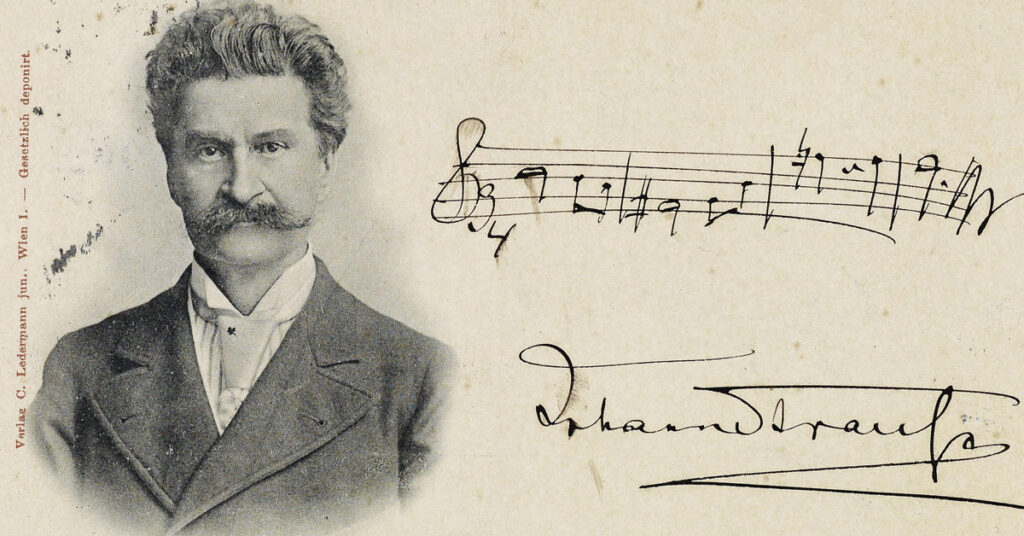

A quick clarification up front: there are TWO Johann Strausses: Sr. and Jr., who are referenced throughout this post. While the younger Strauss has thoroughly eclipsed the elder in popularity and acclaim, both were shining stars of the Viennese musical firmament both in their day and beyond.

If the question is: how do you rise head and shoulders in popularity over contemporaries like Brahms, Schumann, Rossini, and Wagner, then the answer is apparently to be a chill guy and not take yourself too seriously. By writing music for parties, dances, and imperial events, Joseph Lanner, Strauss the elder, and Strauss the younger carved out a practical musical and economic niche that insulated them from any expectations of artistry or the haughty nonsense that come with that sort of thing. Along the way, their music swept away not only hometown Vienna, but spread like a wildfire across the European continent and even to the USA.

“Ahh I love this stuff!!!”

— Bramwell Tovey to yours truly, overcome with emotion after conducting Lehár with the New York Philharmonic

One could be forgiven for thinking that the waltz form, as exemplified by the heroes of this blog post, rose through spontaneous generation from the very cream puffs and perfumed silk kerchiefs that swirled around the ballrooms of upper class Viennese. There is no doubt that the sensibilities and qualities of the Viennese dialect, culture, and undertones of Weltschmerz infused the moods and melodies of the waltz. But it was through the very deliberate and somewhat blue collar musical labor of Strauss Sr. and Joseph Lanner, that the distinguished Viennese waltz came into practice. Strauss Sr., through his militant rehearsal methods, extensive touring, and unvarnished compositional approach, distilled and married the component elements of the waltz form to his own voice so completely, that he could adapt them to an endless number of musical or programmatic occasions, without losing their Straussian flavor.

There already existed a great deal of 3/4 time dance music in Vienna at the time: ländler, German dances, minuets, folk music, and the “closed position” of the dancers had been scandalizing the older generations for two decades before Strauss Sr. was born in 1804.

Strauss Sr. should never have ended up a musician. His innkeeper parents were troubled by his early artistic aspirations, fearing the prospect of their son becoming a “dinner musician (Abendsmusiker),” or someone who performed all day and night at a restaurant or casino, in exchange for food and lodging. Such was, in their minds, the best case scenario in the career of an aspiring freelancer in those days. But fate intervened, and Johnny’s (Schani’s) early and amateur efforts on the violin were deepened by a fortuitous meeting with the teacher Johann Polischansky, who put him on a path towards musical relevance. The rather humble musical training that Strauss the elder received would later be put into stark contrast with that of his son, whose sophisticated musicianship afforded him a much more varied and ambitious compositional palette.

It should also be noted, that Strauss the elder put up extraordinary resistance to the idea of his son becoming a musician. This was no passing fit of misguided paternal career advice; Papa Strauss took extreme measures to prevent (and would later work to sabotage) the musical growth of his son. But persistence paid off for Jr., and on October 15, 1844, Johann Strauss Jr. led his very own orchestra in a debut at Dommayer’s Casino which would ultimately lift the careers of both father and son.

So where to start?

Just start with the so-called “concert” waltzes of Johann Strauss II. The Blue Danube, Künstlerleben (Artist’s Life), and Voices of Spring are some of my favorites, and it’s hard to go wrong with any of them. The polkas, galops, and marches are similarly addicting.

Erich Kleiber seemed to maximize the rubato aspect of the music, working wonders of rhythmic control and timing in his recordings:

Don’t forget about Die Fledermaus – if you have a free afternoon bask in it’s shameless fun and richly varied score. It’s a great reminder of how complete of a composer Johann Strauss II was, even if he’s typecasted as a musical comedian.